Lauren Groff

Arcadia

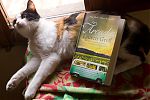

Arcadia by Lauren Groff was one of the books I bought when I was in the States a few months ago. The title and trippy cover (not mine) seemed to be all over the book websites for a time, and talk has dwindled since then but not quieted. Sometimes I think I would have been a better hippie than a 21st-century expat, so Arcadia, its setting on a commune, tenaciously stuck in my mind and I had to read it.

Arcadia spends half the book in the commune, Arcadia, and the other half in the Outside. It follows the life of Bit, born while the commune was still a caravan, in four parts divided by his ages of 5, 15, 30, and 45 (or so). The opening of the book is soft and mythic, telling the story of the caravan of Volkswagen buses and other vans when Bit was in utero.

This is Bit’s first memory, although he hadn’t been born when it happened. Still, the road winding through the mountains is clear to him, the rest stop with the yellow flowers that closed under the children’s touch.

As a child, Bit has an innocence that lends even more of a golden glow to the commune’s ideals, which combines with Lauren Groff’s rich language to create an indelible dreamscape of communal perfection and harmony. It was the livingness of these ideals—the Free People working in the fields, birthing their own babies, living with whomever they pleased—and the eventual disintegration of these ideals that I found to be one of the most fascinating layers of Arcadia. And because Bit is the narrator, the inevitability of Arcadia’s fall isn’t as inevitable—not that anyone else would admit to the defeat built into success. Far at the end of the novel, the Amish woman Glory says Arcadia failed because of its freedom:

Too much freedom, it rots things in communities quick. That was the problem with your Arcadia.

While Bit believes the rift that tore Arcadia apart was formed out of Handy’s pride—the leader who gets all the praise and then all the blame. That it didn’t work out brings up questions about if such perfection is even possible. Handy’s daughter Helle, whom Bit falls in love with, remembers her childhood in Arcadia as something not worth remembering, as a cold and hungry time when every night she had to listen to people fucking. But Bit’s memories of Arcadia are firmly the opposite; his family was a stable one, which probably made a very big difference.

Once the commune dissolves and its members are spread around the Outside, Bit is never able to again touch the ideal and beauty of life so strongly set into the already ideal of childhood—except through art, photography. There is a lot of sadness in this half of the book; partly it comes out of Bit’s sensitivity and his perceptions of the distance between people, and partly it comes from the tragedies that would sadden anyone.

Yet the book doesn’t waddle in hopelessness. The stories that were told and shared by all of Arcadia, like the memory of the caravan, were part of what drew the people of Arcadia together. And it is these stories that can be told anywhere, between anybody, and it is the stories that have the strength to hold people together over distances.

It isn’t important if the story was ever true . . . he knows stories don’t need to be factual to be vital. He understands, with a feeling inside him like a wind whipping through a room, that when we lose the stories we have believed about ourselves, we are losing more than stories, we are losing ourselves.

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·