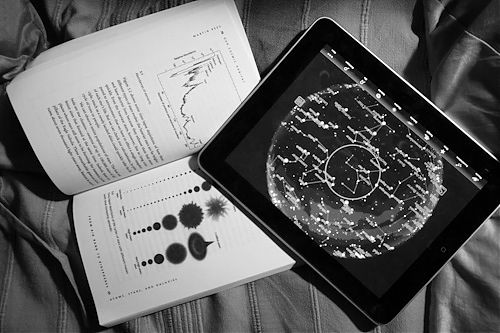

Martin Rees

Our Cosmic Habitat

I am not a scientific type of person. Science rarely excites me and seems inaccessible but to those who “get it.” It is good for us then, if you are like me, that we have scientists like Martin Rees, who find it important that laymen may make a slight step from zero understanding to a little bit.

I didn’t finish Our Cosmic Habitat with a glowing comprehension of our universe—it is written for scientists as well—yet a little understanding feels like a lot. And why not? If I would have come across any cosmologist six months ago, I would have seemed as dumb as a duck, but now, at least, I have questions and am curious. And how could I not be? The universe is loaded with questions and answers and unapproachable answers and unthinkable questions in a space so vast, or so infinitesimal that my mind flounders merely at its edges.

That’s one thing I learned right away: these numbers are really big, or they’re really small. Who knows how long the speed of light is? Should I be able to measure it, imagine it? For when the lights arrive here from the dawn of universal creation, does that really make any concept any clearer? I have to trust in Sir Martin Rees.

I also learned right away that Martin Rees believes our universe is governed by laws puzzlingly biophilic. Though human existence (and life in general) is a result of time and chance—imagine if that comet didn’t send the dinosaurs into extinction—life itself seems strangely accounted for. Which sends me into all sorts of literary exclamations: Life and Life abundant! We must enjoy our time here in the Local Cluster for my god is it short.

Our universe is 13 billion years old. All of human life so far is but a blip. Yet human complexity rivals the laws of stars.

Under extreme conditions—inside the stars or in the hot early universe—everything breaks down to its simplest ingredients. A star is simpler than an insect. Biologists, tackling the intricate multilayered structures of butterflies or brains, face tougher challenges than astronomers.

Yet:

It is embarrassing to cosmologists that 90 percent of the universe is unaccounted for.

There’s dark matter in the cosmos and there’s black holes. There’s gravity and anti-gravity, there’s hydrogen and nuclear fusion and pulsars and interstellar gas. There’s electrical activity and radioactive activity and other activities unknown. There’s acceleration or deceleration, expansion and other forces unseen. And there’s us.

Advances in technology bring the astronomers nearer to the question that has bothered them the most since the answers of quantum mechanics. They are searching for unified theories of the cosmos and microworld. Or, a “Theory of Everything.”

But what seems to interest Martin Rees more is the possibility that our universe might be part of a multiverse. He painstakingly details how a such a multiverse cannot be ruled out; and imagines our Big Bang as part of a series of Big Bangs, much as corn kernels explode in a hot pot, I guess. If Martin Rees is right, then for some reason, I would be very happy.

There’s something very reassuring about a multiverse. Not that our universe is too tiny, but there is grandeur to the possibility. I shudder when I think of what we’ve done to the benevolent Earth with our petty complexes of power and control. In a multiverse our harm seems more likely to be forgiven, for life might exist outside this orbit. How fascinating!

Commentary for Our Cosmic Habitat

Dear Pippa, It is indeed hard not to think of questions like yours when reading about the mind boggling smallness of our universe. Last night I picked up Carl Sagan’s The Cosmic Connection, which I think, is his opinion in these matters. And how do we know? Sometimes I think human intelligence isn’t ready for answers! Thanks for the provocative questions!

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

1 On Monday 03 January 2011 Pippa Soundy wrote:

Do you think the other universes might have something to do with us? I mean, do they interact with ours in ways impossible to measure because they are governed by other ‘numbers’? Could they be what we sometimes think of as ‘supernatural’ or ‘spiritual’ dimensions? They may have life of their own, but do our lives transfer to another universe when we die?