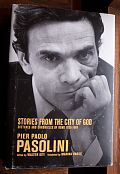

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Stories From the City of God

Sketches and Chronicles of Rome 1950-1966

Henry Miller once wrote that one of the best rewards of reading is discovering a poet who thinks. And Pier Paolo Pasolini is firmly in this illustrious category. Not only was he a poet, a film director, script writer, a novelist, a social commentator, but he also adhered to a life philosophy that is self-evident in the short pieces of this tight collection, Stories From the City of God. He was anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist, anti-Americanization and anti-gentrification and he was horrified at the end of his life (which was not a natural ending) at what had become of his beloved city of Rome.

The collection is divided into two: sketches or short stories, and chronicles or journalist observations. Every piece illustrates Pasolini’s Rome, post-war Rome, Rome of poverty, of dialect, the periphery and his favorite subject, the ragazzi. Ragazzi populate the first half of the book; they are the reoccurring characters of his stories and novels. As Pasolini wrote in Trastevere Boy, and repeated, in some form or another throughout: but where does the Tiber end and the boy begin? Where does Rome end and the boy begin?

The ragazzi are young, poor, and Roman. They live on the outskirts of the city but also in the center. When asked why Pasolini searched out these areas, he replied that when he first came to Rome he was poor too. And then there were erotic reasons—assumed but not written—that followed a Greek leaning.

The Rome that these ragazzi inhabited is gone now, but survives in the Roman dialect, which is something alive and always changing.

Roman dialect is in most cases a form of slang. It is inconceivable for a Roman speaker, especially if he is young, to express a complete thought without using “expressive emphases” and without making use of “vivid” vocabulary… Roman slang depends on this fundamental “narcissistic fixation” in the average speaker, and his consequent exhibitionism. — Roman Slang

The Rome of the post-war years was proletariat and sub-proletariat, there were slums and the displacement enforced by the projects of Mussolini. People swam in the Tiber (che schifo!) and rode their bikes south to Terracina. Terracina was probably my favorite piece in the book for its length brought a strong development of character and setting; character and setting woven so finely out of the poetics of Pasolini’s prose. His descriptions are so loving and living they seem to jump off the page.

Now, many of the situations Pasolini describes, the poverty and the squalor, the chestnut and flower vending, do not belong to the Italians, but to the immigrants from Bangladesh or Africa. Rome has changed considerably since the time of Pasolini’s stories, the 1950s and 60s. In the interview at the end, Pasolini bitterly describes Rome of 1973 as a small, bourgeois, provincial city. And that’s true, especially in the overpriced center.

But Pasolini’s Rome does still exist in some ways. Because though ambitions and ideologies have succumbed to the irresistible movement of globalization, there are pockets within Rome that remain, in their own particular way, Roman. A proof of the Roman capacity for survival is in their resistance to the centuries of domination by the powerful Vatican. Rome and the Romans operates on their own moral code, and will continue to, or I hope so.

(For more books and novels set in Rome, see my list.)

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·