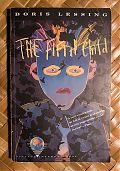

Doris Lessing

The Fifth Child

Over and over in interviews Doris Lessing has insisted that The Fifth Child is not “about” anything: it’s not “about” the Palestinian problem, genetic research, feminism, and anti-Semitism and so on.1 Perhaps The Fifth Child has been “pigeonholed” so often because it is what it is: a good story. “I am a storyteller,” Doris Lessing says.

And it is no one but Doris Lessing who could have told the story of Ben, the fifth child. And before Ben’s birth, no other writer could have created in less pages, his blissfully happy family. Harriet and David were meant for each other, born for each other, for who else in this world wants to fill a massive house with loads of babies? They want to prove that their differences are not different but the essential ingredients to make The Happy Family.

Harriet and David succeed. All too well really, for from the outside the cycles of babies and holidays does look carefree and comfortable. They have made a family others want to be part of, a family that looks like perfection. Even Harriet, who has given birth to four kids, breast fed them, raising them one after another, doesn’t feel discouraged. Let the babies keep coming!

The fifth child, from the start, is not like the others: a monster. In the womb he struggles and beats Harriet’s insides black and blue. It is during this pregnancy that the narrative shifts from the family, Harriet and David, to only Harriet. For only Harriet bears what is within her, only Harriet can make any guesses.

Her time was endurance, contending pain. Phantoms and chimeras haunted her brain. She would think, When the scientists make experiments, welding two kinds of animals together, of different sizes, then I suppose this is what the poor mother feels.

Then Ben is born. He’s not a monster but he’s not really a baby either. Harriet thinks he resembles a mythic creature like a goblin, or is an evolutionary throwback from antediluvian times. Extremely active and strong, rigid and ungiving, Ben is the alien who destroys the happy family.

By some force of will, Harriet commits herself to Ben, to raising him if that’s what it could be called. Through Ben she wears herself thin and secludes herself, the pariah of the family. She doesn’t take care of Ben out of maternal love, no, she does it for some other reason, some kind of unspoken rule she must uphold. For from Ben there is never any thankfulness, no feeling, and neither from her family.

Harriet takes Ben to doctors, then later on she has brief talks with his teachers who all consent: “Oh, he’s just active. You’re not the only one. It happens all the time.” Rare is the person who can admit Ben’s obvious difference. Yet Ben has an effect on them, an effect no one is quick to admit, he scares them for unthinkable, unvoicable reasons. It would be easy to conclude that Ben is evil, striking discord, breaking things up but he’s not. As Doris Lessing insists: he is simply misplaced. In the wrong place at the wrong time.

As the novel read speedily on, I began to like Harriet more and more. She didn’t sit well with me in the beginning, her prudish virginity, the big house, David and her stubbornly held dream. But it all shatters and Harriet becomes someone else, stronger, independent, with new ideas about the world and her own ideas about Ben that she insistently defends.

The Fifth Child read quick, without any chapters to break up the story. Doris Lessing seems to carry the reader along, happily and then fearfully, until before you know it, you’re done and you feel relief that it was only, thankfully, a story.

1 From Putting the Questions Differently, Interviews with Doris Lessing

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·