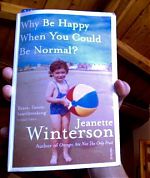

Jeanette Winterson

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

I bought this book in early spring in London. Right after crossing the bridge from the Tate Museum there was a man selling books off his blanket. I reached for Jeanette Winterson’s autobiography immediately, having had it in my sight since it was published. When it was published it garnered lots of praise, and I love reading writers’ autobiographies for those formative inclinations towards writing.

There are many beautiful things about this book. It’s structure shuns chronology though it still manages to follow it in a logical way—from birth to the meetings with her biological mother much later in life. Winterson’s novels play with time and so does this autobiography. She explains the two types of time as

linear time, that is also cyclical because history repeats itself, even as it seems to progress, and real time, which is not subject to the clock or the calendar, and is where the soul used to live. This real time is reversible and redeemable.

And it is in real time that much of this book must have been written in because it is a story of self-redemption through writing and living. While reading, I had the impression that this process was happening right under my eyes, that Jeanette Winterson was writing to clear out all her painful memories of growing up with her adoptive mother, and all its repercussions, to make room for the best part of herself—the one that can regenerate, not destroy.

Creativity is on the side of health—it isn’t the thing that drives us mad; it is the capacity in us that tries to save us from madness.

It seems inevitable that Jeanette Winterson became a writer. She began by reading stories as an escape, but soon found that they also offered alternatives. The stories in books could be built upon, and they ran parallel to her own life. Winterson used to hide the books she bought under her bed because her mom forbade her from reading much else besides the Bible (though she avidly read murder mysteries). But her mom found the books, tossed them out the window, poured gas on them and threw down a match. From that point on Winterson memorised the stories she read and began to write her own.

Telling stories is also a way to “exercise control.” To take back what is “unfair, unjust, unknowable, out of control.” They are a way of organising our lives into some kind of meaning. They give sense to pain and a definition to suffering. And if anything, that’s just what Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? does, but with love and humour and in elegant sentences.

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·