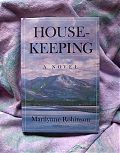

Marilynne Robinson

Housekeeping

On finishing Housekeeping I was left with the sense of having been haunted. Marilynne Robinson’s prose moved along with such a lack of pretension, with no flashing grabs for attention like ripples of the lake that stood at this book’s center; I could have enjoyed this book by only the sounds of its composition. But behind its rhythm were the images, and it is these that keep on rising.

I must assume that Marilynne Robinson was also haunted.

But every memory is turned over and over again, every word, however chance, written in the heart of the hope that memory will fulfill itself, and become flesh, and the wanderers will find a way home, and the perished, whose lack we always feel, will step through the door finally and stroke our hair with dreaming, habitual fondness, not meant to have kept us waiting for so long.

Housekeeping is a book populated by women, which I suppose the name implies. The only men to show up in these pages are authority figures and the grandfather who chose Fingerbone as a town to live in. It’s appropriate that a man would have chosen this harsh, cold place dominated by the lake which was to be his death. For the women who go on living in that house he built are as at home there as if they were the tropics.

The girls, Lucille and Ruth, who were first raised by their grandmother, then her sisters-in-law then her daughter Sylvie, never had much use for the town of Fingerbone anyway. In particular, Sylvie, Lucille and Ruth were drawn to the lake. The lake was large of size and loomed large in the book as well, an immensity which pulled everything else in Housekeeping to its fringes.

The lake and windows and transience and memories and Ruth goes between these trying to tie up loose ends.

For why do our thoughts turn to some gesture of a hand, the fall of a sleeve, some corner of a room on a particular anonymous afternoon, even when we are asleep, and even when we are so old that our thoughts have abandoned other business? What are all these fragments for, if not to be knit up finally?

Housekeeping must be finished knitting. For how confusing it must have been to be Lucille and Ruthie, with important people always dying or leaving. Their whole lives a transience or a rebellion of that which never stays, afloat on the fickle tides of memories, trying to piece themselves together with the material available.

It has been said that in Housekeeping there is not much that “happens,” which can only be a complaint about this book’s masterfully deep subtleties. There is so much layered in this prose, much that “happens” without being said, layered like the lives of a lake, that to judge the obvious surface value is just shallow. Housekeeping is a book that expects the reader to make the connections, to look out a window blackened by the inside lights and not only see one’s own reflection.

Which is probably why I enjoyed Housekeeping as much as I did. It’s a book that stayed with me; and that which I didn’t even realized to have read rose like deep-water bubbles to the surface.

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·